Jack Jackson, a traveling salesman, always sold his quota of elephants: the customers liked him and he knew how to excite a quick win-win deal. He always thought to mention to prospective customers that he was putting his dog through university. And, in tough cases, he would add sadly that his alligator-in-law had been deep in bed with a severe case of rick-rack for more years than he would care to mention. The sympathetic consumers would turn their heads to the side, tweak their dry nostrils and reluctantly order an elephant—nothing fancy just a small compact model. Mr. Jackson would thank them and quickly pull the installment contract out of his bamboo brief case.

Once, when he’d been a bit tipsy on beet juice, Jack had confessed to a colleague that he had no connection with dogs in or out of university and that he had never even seen his alligator-in-law, although he had faith that he had one, somewhere. “But,” Mr. Jackson glowed,” Business was business” and he had to feed himself and his rather robust little wife.

It is an hysterical truism to say that times were difficult in Jack’s day and age. The economic climate had changed since old Mr. Jackson, Jack’s father, had been a successful lawn-mower salesman. For one thing, there was no longer any grass to speak of; it was a closed subject. All available blades had been converted into mats and traded with the enemy for china thimbles, a commodity the nation swooned for. Secondly, all the straw not suitable for sale abroad was being used for houses. So what was one to recommend as food for an elephant unless you knew of a spare straw house that could be rationed out for consumption.

It was true that people had been crying out for elephants a few years earlier but that was before the housing boom had used up most of the countries‟ straw. An average elephant, without being a pig, could eat a man out of house and home.

Although the nation loved and admired elephant salesmen and everyone considered it was wise to know at least one, Betsy, Jack’s wife, had never been pleased about her husband’s profession. It was the product not the prestige that Betsy objected to. She was not partial to elephants. Only great loyalty had kept her from confessing her distaste to Jack.

Over the years she had bravely attempted to be civil to the elephants that Jack brought home and to react in a charmingly enthusiastic fashion whenever the topic came up. After all elephants were Jack’s life. Betsy suspected that she would have had a happier life if her husband had sold Ferris wheels or bottle caps but he didn’t and that was that. The fact remained that although she hated elephants she loved Jack. Result—her lips were sealed.

Jack also had a skeleton in his closet that kept him tossing and turning long into a hot night. His guilty secret, that no one except the occasional elephant guessed, was that he didn’t like elephants either. In fact at times he could hardly tolerate them. They made him sneeze and turned his knee caps mauve. Fortunately in his business he was always required to wear long pants; had Bermuda shorts caught on his career would have been ruined.

All through the years Jack had born this horrid cross. Eventually he could bear it no longer. Just before his fourteenth year as an elephant salesman Jack decided to ask to be transferred to another department. He’d say he wasn’t as young as he used to be and that he couldn’t move elephants like he’d done in the old days. He thought it wiser not to tell Betsy until it was all settled and then there’d be fewer questions.

His only concern was that Betsy really enjoyed a good elephant; the greyer the better, she’d often say. It was unfair to cut her off completely. If the company did agree to move him to the button-hole department or carnation stems Betsy’d have seen the last of the elephants. If you didn’t sell ‘em, you didn’t see ‘em—that was the law. The elephant room was always locked; taboo to non-salesmen. There wouldn’t even be an occasional elephant to drop over for tea.

Loyal husband that he was, Jack realized that his decision was selfish but he just couldn’t bear to go on selling those dreadful beasts. After much fretting Jack finally came up with an idea: a stuffed elephant. Yes. Why not? He’d buy Betsy an authentic perfumed stuffed elephant all her own. Something to keep her company all day as she patched. Something to fill up the house and filter the sunshine. Brilliant idea if he did say it himself. Better than roses, a stuffed elephant didn’t fade or lose its petals.

So on that fateful day when Jack was officially transferred to the fringe unit, he invested five dollars a week until death in the largest grittiest elephant ever stuffed. He kept it all top secret and planned never to go into Betsy’s sewing room after the gift was delivered.

Betsy, as all good wives, knew that Jack was changing jobs before he did. She imagined it was because he was no longer the speed skater he had been and she felt sad. She didn’t mention it to him but late at night wooed to sleep by waves of Jack’s rough snores she worried about how her poor husband would manage without his grey friends. For her, it would be a relief. No more massive grey feet plodding across the vestibule or dirtying up the rugs, no more straw cakes to be served at tea, no urgent late night calls from a desperate customer with a faulty elephant. But for Jack it would represent the loss of youth and a lonely old age. So Betsy, loving wife that she was, decided to buy Jack a small compact elephant from his associate Ed Krinkly. A comfy economy model for Jack to read the paper by and spend a Sunday with.

The deal was quickly arranged and the gift was to be delivered the very day Jack was transferred. The day that Jack left the elephant promotion department there was a commemoration dinner at tea-time. There were serpentines, walruses and champagne. After everyone had eaten their thirst away there were speeches. The motley crowd felt a little sad for good old Jack—past his prime he was. “Never thought Jack would give up his elephants,” they muttered through their cream cheese sandwiches. The big boss, Mr. Knottle, wound up the celebration with a sensitive traditional oration which included the popular elephant myth, a cherished tale to all elephant lovers. The story explains how an elephants can detect sincerity and how an elephant exposed to a human who dislikes him for more than 12 hours straight will explode in a volcanic burst, his remains covering the area in thick pink fluff. Everybody chuckled at the favourite old story. Many didn’t doubt that it was true. Elephants are shrewd. I wouldn’t put it past them as one man commented.

When Jack arrived home there were two elephants and one proud wife to greet him. The elephants had been delivered at five-thirty exact. One was stuffed, the other hungry.

“What a lovely surprise,” Jack choked when his wife had introduced her gift.

“Great minds think alike,” wept his wife.

After the elephants were seen and seen to, the anxious couple settled down to a quiet supper. Both were openly pleased with the other’s gift and looked forward to a short happy future. They talked about the elephant tale and laughed self-consciously. Imagine anyone not liking elephants. Those darling grey beasts. Was it possible? Why Jack was as sure that his wife loved elephants as he was that she loved him. Yes, Betsy felt the same way about her husband. If she doubted Jack’s love of elephants she would have to doubt the sun. They both laughed again glancing over their shoulders at the munching grey beast who stared mutely at them from the other room. shorts caught on his career would have been ruined.

Jack and Betsy went to bed early but they couldn’t sleep. They tossed and turned. Eventually Betsy had to get up and remake the bed, carefully tucking the covers in at the end. What a silly old myth one said, and they laughed. Why think of it? One shrugged. Good night. At last they both lay quietly, pretending to be asleep. Hours, like years, of quiet listening rolled over them. They floated along inside their own skin listening to the other’s breath. The feeling of guilt slowly crawled over them like tiny spiders. About five o’clock they both had fallen off to ragged sleep.

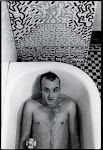

At five-thirty they were awakened with a bang. The house shook and then Jack and Betsy were asleep again hibernating for life under a sea of pink fluff. Melodie Corrigall ignores pundits' advice to write about what you know. She has never owned nor sold an elephant, but being an existentialist, skilled at making snow angels, she emphasizes with Jack Johnson's angst. Her writing has appeared in The Dalhousie Review, Toasted Cheese, The Blue Lake Review, November 3rd Club, Halfway Down the Stairs and Subtle Fiction. This Zine Will Change Your Life previously published The Circus and The Library by Melodie Corrigall. Check it out. Photo by Adam Lawrence.

Street art by Appa the Dancing Elephant.

No comments:

Post a Comment