Outside things seemed to be dying under the cold rain. This even though it was summer again. Clouds moved slow across the sky like old stubborn men. I filled a garbage bag with old sheets, towels, and rotten food and took it outside to the dumpster.

When I got back upstairs the place looked clean and new like I’d never remembered it, like there was a window in there that I never knew about and that was finally opened. I walked around in there and tried to soak up the feeling.

After a while I went outside again to smoke a cigarette. There was a woman down there. She came to me. She was holding one of the books that I had thrown away in the garbage bag.

She said, “Do you know Erica Walker?”

“No,” I said.

The book wasn’t mine. Really. I found the book when I first moved in. I just never got around to throwing it out before. The woman opened it up to show me the place where Erica had written her name.

“This book was on top of the cans,” the woman said. “She’s not listed in the directory in the lobby, and she’s not in the phonebook.”

“I don’t know her,” I said.

“It’s a perfectly good book,” she said.

“I see,” I said.

“I guess I’ll just leave it on top of the cans, in case she realizes and looks for it,” she said.

“All right,” I said.

She turned around to put the book back, so I hurried into the building and into my apartment. I don’t know why the woman lied about finding the book on top of the dumpsters. I guess it doesn’t really matter now. The next time that I went down there to smoke, the woman was still there, poking around in the cans.

I felt bad and said, “I lied to you before. I threw the book away. Erica lived in the apartment I live in now.”

The woman said, “Oh.”

“I don’t know why I lied about it,” I said.

I waited for the woman to tell me that she had gone through my bag of garbage, but she didn’t tell me anything. From what I could tell, she was going through the dumpsters to find recyclables that had been misplaced. She was old, I could tell. I could tell she was much older. I watched her as she kept examining the big cans of garbage. Right then that older woman looked so beautiful and helpless that I probably should have killed her then and there.

Instead I just wandered around Brady Street, where the people crowd together. It was raining still. When I got to a bar that looked mostly empty, I went inside. The place was smoky and dark. There were two men at one end of the bar, hunched down over themselves like they were trying to think their way into their own bodies. The man behind the bar was hovering near them, watching their drinks more than the men. A fourth man and a woman were dancing in their own way near the jukebox.

The man behind the bar brought me a beer and an ashtray. He talked to me in a soft voice, like he read something terrible on my face. I didn’t really believe him. I felt fine.

Eventually he said, “How’s things.”

So I said, “My girl just left me.”

The truth was I had no girl. Part of me just wanted to say the word.

“Breaks,” he said.

“You’re telling me,” I said.

“What happened?”

And then one of the guys at the end of the bar coughed something up, and the man behind the bar walked away to make sure he didn’t make a bigger mess.

The man who coughed just kept saying, “All right, all right.”

I was nodding off, with no idea of how much time had passed since I had come in. I was soaking wet from the rain, even after the time spent drinking all of the beers in front of me, so I decided to go to the bathroom to dry myself with some paper towels. Inside was the man who had been dancing with the girl. He was looking out of the window that was above the bathroom sink. I walked up behind him and looked over his shoulder.

He said, “That’s my wife there.”

The man scooted over to let me have a better angle in the window. There was a woman, the one he had been dancing with I guessed, standing out back with another man. They were kissing against a tree out in the rain.

“Are you sure?” I asked.

“She was here with me,” he said. “I came in here, and then I saw them through the window just walking out there.”

I studied the guy. His shirt was unbuttoned a little, and his pants were unzipped.

“What do I do here?” he said.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Shouldn’t you go out there and do something?”

“I haven’t seen her all wet like that in a long time.”

“She looks kind of amazing all soaked,” I said.

“Yeah,” he said.

“Probably we all do, though,” I said.

I wished that I could remember seeing the woman leave. Maybe she had gone with one of the other men at the bar, or maybe it was the man behind the bar. I don’t know how I missed it. Where did it all go? But whatever it was I couldn’t remember it.

Without knowing why, I locked the door behind the man and me. He lit a cigarette and puffed at it, still fixed on his wife and the man by the tree.

“I don’t think you can smoke in here,” I said.

“I’ve been having this dream,” he said. “I’m flying through space, and then I land in a forest on another planet. It seems weird that there are forests on another planet. I try to breathe, but I can’t. All the oxygen was sucked out of me forever while I was in space.”

I said, “I’ve had that dream, but mine is a little different. In mine, I’m underwater.”

“Sucked dry,” he said. “Underwater. Think about that.”

He looked at me. I thought about it. Outside the woman and the man were losing steam. The weather was clearing up, the sun starting to peak its head through the clouds like a newborn. When the man’s wife was gone, the man turned from the window with a look on his face like he had actually fallen through the glass. He walked out the door, and I realized that what I thought was the lock was just a useless lever. I stayed by the window, waiting to see if the dancing, dreaming man would walk out there, either to follow his wife or just stand sad by the big tree. I never saw him. When another man came into the bathroom, I nodded and then left.

So it goes.

Timothy Raymond grew up in southeastern Wyoming. Currently he studies contemporary American literature at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, where he also teaches writing. His stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Necessary Fiction, The Owen Wister Review, Bartleby-Snopes, Word Riot, Writers’ Bloc, and others.

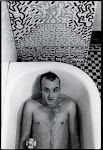

Photograph by Adam Lawrence.

Street art by A.S.V.P.

On April 20th, the debut album of this Ethiopian born singer will change the way you experience music. Meklit Hadero has a voice that can make time stop.

No comments:

Post a Comment